by Michael Adams, Chief Executive Officer, SAGE

These interconnected challenges result in significantly higher levels of financial insecurity, thinner support networks, powerful barriers to accessing services and supports, and heightened fears of aging among older LGBTQ people. Barriers to successful aging have been made much worse by COVID-19, which has had a devastating impact on older Californians, especially among Black and brown elders. While California has made meaningful progress in recent years through a series of important policy steps designed to address the needs of LGBTQ older people, much more needs to be done.

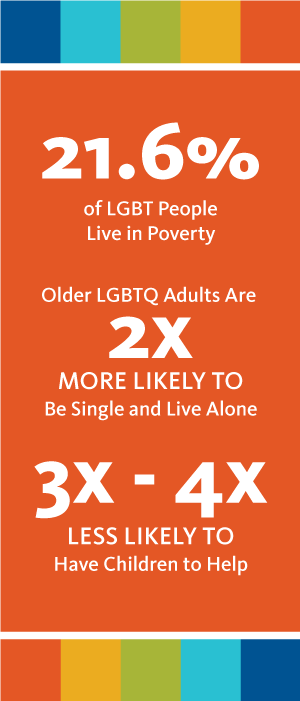

Beyond financial disparities, LGBTQ older adults also face high levels of social isolation. LGBTQ elders are twice as likely as cisgender heterosexual elders to live alone, twice as likely to be single, and three to four times less to likely to have children. Given these statistics, it is not surprising that 50 percent of LGBTQ older adults report feeling isolated from others. Many age with very thin support networks. For example, 25 percent of older LGBTQ people served by SAGE have nobody to contact in case of an emergency.

Discrimination and stigma also are a huge challenge. For example, 48 percent of older same-sex couples face discrimination when applying for senior rental housing. On average, LGB older adults report six incidents of discrimination over the course of their lifetimes; transgender older adults report 11 incidents of discrimination. Incidents of discrimination, especially when combined with other vulnerabilities like financial insecurity and isolation, can lead to internalized stigma that results in negative health outcomes like higher levels of mental health issues and substance abuse.

In light of this daunting panorama, it’s not surprising that LGBTQ older adults have much higher fears of aging than older Americans in general. Fifty-one percent of LGBTQ elders are concerned about having enough money to live on as they age compared to 36 percent of their heterosexual cisgender counterparts; 30 percent are very or extremely concerned about not having someone to care of them as they age, versus 16 percent of their non-LGBTQ age peers.

In response to this backdrop, California has made significant public policy progress in recent years by enacting legislation that designates LGBTQ older people as a priority population for state aging services, and that protects LGBTQ older people and those living with HIV from discrimination in long-term care. In addition, California now mandates LGBTQ “cultural competency” training for aging service providers, long-term care workers, and residential care facilities for the elderly. Moreover, California now requires LGBTQ-inclusive data collection; importantly, this includes the collection of transgender-inclusive health data. And, California has been a leader in offering LGBTQ-friendly affordable elder housing, with five of the country’s 11 such housing developments currently in operation located in the state. Those developments – sited in Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco – provide 448 units of LGBT-friendly elder housing, with another development slated to open soon in Sacramento.

While this is important progress, much more needs to be done. One key is implementation – prioritization of LGBTQ older adults in aging services and anti-discrimination protections are useful only to the extent that they are enforced. In addition, “cultural competency” training mandates must be enforced and extended into home and community-based services. California needs to advance policies and funding to promote social connectedness and prevent social isolation among LGBTQ older adults (and older adults more broadly). Recognizing that one of the most serious health disparities that LGBTQ elders grapple with is higher levels of HIV/AIDS, California must move to designate older people living with HIV as a priority population for aging services and must encourage HIV testing among older adults. Throughout these policy moves, there must be a particularized focus on older lesbians, transgender and gender non-confirming elders, and LGBTQ elders of color. And the state’s pro-LGBTQ aging policies must take account that 29 percent of LGBTQ older adults live in rural areas, and they face higher levels of poverty than their rural age peers. Given this, there must be a concerted effort to extend training, as well as LGBTQ-friendly elder services and housing, into rural parts of the state.

In sum, LGBTQ older adults in California face unique challenges as they age. While California has taken important initial steps toward addressing the needs of this highly vulnerable group of older Californians, much more remains to be done. Fortunately, LGBTQ elders know what progress looks like and LGBTQ aging advocates have identified the steps that need to be taken. If we work together, we can break through the barriers to successful aging for LGBTQ older people and build a more equitable aging future for all older Californians.

As we look to the future and consider what steps we need to take to build aging equity for older adults in California, the realities and needs of particularly vulnerable populations must be high on our collective radar screens. One such population is LGBTQ older adults. There are more than 500,000 LGBTQ older people in California, and that number is growing rapidly. As a group, LGBTQ older adults face unique challenges to successful aging, including the cumulative financial (and psychological) effects of lifetimes of discrimination, high levels of social isolation, and the current impact of unequal and inequitable treatment by laws and programs designed to assist older adults.

As we look to the future and consider what steps we need to take to build aging equity for older adults in California, the realities and needs of particularly vulnerable populations must be high on our collective radar screens. One such population is LGBTQ older adults. There are more than 500,000 LGBTQ older people in California, and that number is growing rapidly. As a group, LGBTQ older adults face unique challenges to successful aging, including the cumulative financial (and psychological) effects of lifetimes of discrimination, high levels of social isolation, and the current impact of unequal and inequitable treatment by laws and programs designed to assist older adults.  One of the reasons why more progress is so important is because many LGBTQ elders are in acute financial distress. Generally speaking, 21.6 percent of LGBT people are living in poverty versus 15.7 percent of cisgender heterosexual people. This trend holds for LGBTQ older adults, with older lesbians, transgender elders, and elders of color faring worse financially. The annual Social Security income of older gay couples is 18 percent less than that of heterosexual older couples, while the Social Security income of older lesbian couples is 32 percent less. Indeed, older lesbian couples are twice as likely to grow old in poverty as older Americans in general. Moreover, transgender people have an especially high rate of poverty at 29.4 percent. And, Black, Latinx and other-race LGBTQ people have higher poverty rates than their same-race cisgender heterosexual counterparts. For example, 30.8 percent of Black LGBTQ people live in poverty versus 25.3 percent of Black cisgender heterosexual people.

One of the reasons why more progress is so important is because many LGBTQ elders are in acute financial distress. Generally speaking, 21.6 percent of LGBT people are living in poverty versus 15.7 percent of cisgender heterosexual people. This trend holds for LGBTQ older adults, with older lesbians, transgender elders, and elders of color faring worse financially. The annual Social Security income of older gay couples is 18 percent less than that of heterosexual older couples, while the Social Security income of older lesbian couples is 32 percent less. Indeed, older lesbian couples are twice as likely to grow old in poverty as older Americans in general. Moreover, transgender people have an especially high rate of poverty at 29.4 percent. And, Black, Latinx and other-race LGBTQ people have higher poverty rates than their same-race cisgender heterosexual counterparts. For example, 30.8 percent of Black LGBTQ people live in poverty versus 25.3 percent of Black cisgender heterosexual people.